“Three things that constitute a physician: a complete cure, leaving no blemish behind, a painless examination.”

… “A few words” from Ireland

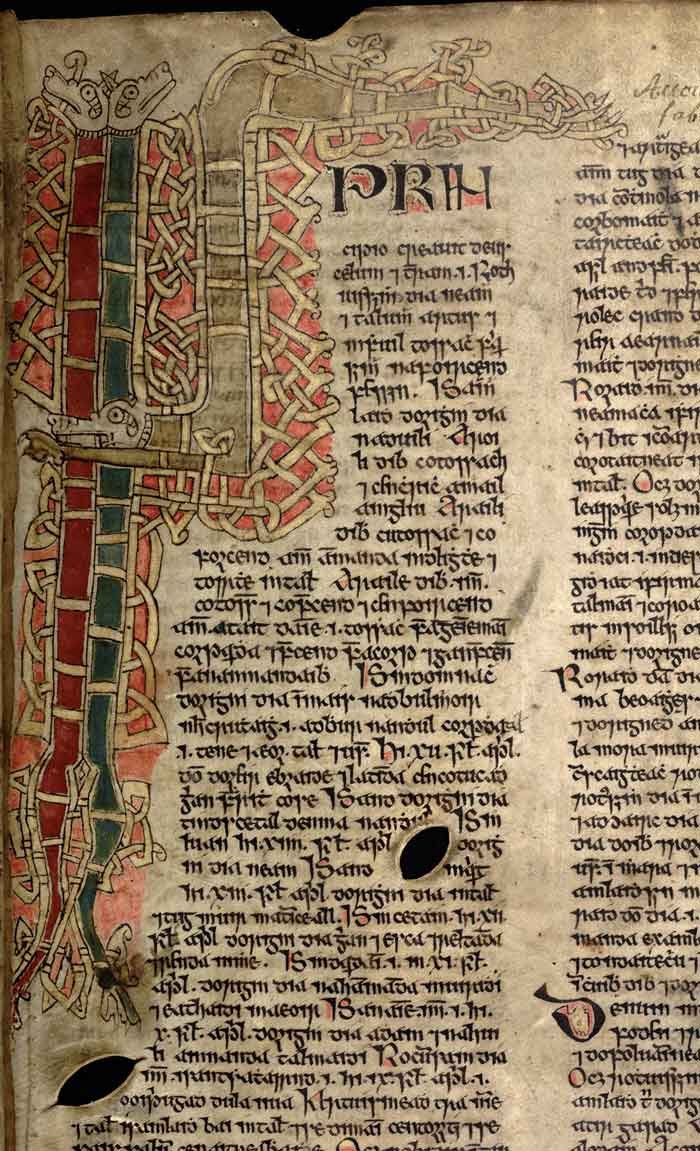

Book of Ballymote Image courtesy of the Royal Irish Academy

This itemization is just one of several hundred “triads” found in a number of Irish manuscripts dating from the fourteenth to the nineteenth century. Triads (and some heptads) were used to recall information to be passed on from generation to generation, and formed part of the Brehon Laws, an ancient, and for many centuries an oral, legal system believed to pre-date Christianity and used in Ireland up until the 17th century.

The Brehon Laws were remarkable in many ways. The fundamental goals were fairness and harmony and learning was revered. The system was hierarchical – the physician ranked lower than the king, the lord, the cleric and the poet – but according to one of the key texts, the Seanchas Már (7th Century AD), “a man is better than his birth”, meaning social mobility was possible.

Fairness and harmony were achieved through a series of fines and restoration rather than physical punishment for crimes – there was no death penalty, for example. While medicine primarily involved herbal remedies, there is evidence that surgery was also practised; the laws state that a physician who cut a joint or a sinew would be fined.

In the case of physical injury, the perpetrator could be required to provide ‘sick maintenance’, which meant caring for the injured person (not just nursing but also providing food and accommodation) and in some cases taking over, or finding someone to take over, their work while they are unable to perform it.

The system recognized the needs and rights of the aged and people with mental illnesses or disabilities who were entitled under the law to care and protection, and made nuanced distinctions such as between those ‘of unsound mind’ who may behave violently and those who were less of a threat.

Women, though not equal to men, were a lot more equal than in many other societies. A woman could divorce her husband for a number of reasons, including his being too fat to have intercourse! She had certain property rights, and if divorced by her husband, was entitled to keep parts of her dowry, especially items related to weaving.

This is too brief a summary to give but a scant idea of the richness of the Brehon Laws. But they represent a part of Irish history which deserves, and rewards, further exploration; the source for this piece, Fergus Kelly’s A Guide to Early Irish Law, is a key text for anyone who wants to know more.

Ireland Through the Lens

Please note, the Irish have a much more ‘accepting’ relationship with strong language than many other nationalities.

The Brehon Laws showed great awareness of the needs of those less able. A number of Irish films have touched on the subject of disability, the most well-known perhaps being My Left Foot (1989) starring Daniel Day-Lewis as Irish painter and writer, Christy Brown, who suffered from cerebral palsy. Cerebral palsy is also the condition of one of the main protagonists in Inside I’m Dancing (2004) while Sanctuary (2017) is a day in the life of a group of young people with intellectual disabilities. In 2023, James Martin, who starred in the short film, An Irish Goodbye, became the first person with Down Syndrome to win an Oscar.

In a different vein (sorry!), A Doctor’s Sword is a film about an Irish doctor with a West Cork (Castletownbere) connection who survived the Second World War. The eponymous sword, the focus of the doctor’s subsequent search, can now be seen, apparently, in MacCarthy’s Bar in Castletownbere.

A Living Tradition

Album cover featuring the band members' dads!

The therapeutic effect of music for patients is not a new concept, but the role of music in the wellbeing of medics is perhaps less examined. During Covid, the Irish Doctors’ Orchestra and the Irish Doctors’ Choir got together online to provide support for those working in the health service during the pandemic. In June 2022, members of the orchestra went to Heir Island off the coast of West Cork to work with local composer Justin Grounds on a piece he entitled Brightly Burning Flame.

On a different note (sorry again!), the Saw Doctors, formed in 1980, are one of Ireland’s longest standing rock bands. Their first single, N17, has a theme common to many Irish traditional tunes: nostalgia for home. Exemplifying that syncretism which is, I believe, a feature of contemporary music in Ireland, in January 2021, Nigerian-born singer from Co Offaly, Tolü Makay, produced a cover version which became the most downloaded song in one week.

Quark

When it comes to medical matters, the Irish have been producing texts since medieval times. The Royal Irish Academy in Dublin contains the largest selection of these, mainly translations of continental tracts. On the other hand, oral tradition has maintained folk medicine lore to the present day.

According to the Irish Times, Eoin O’Brien’s A Life in Medicine: From Asclepius to Beckett (2023) is a “[c]ompelling and fascinating biography that illuminates Dublin's bygone medical and literary circles”, while more controversial discussion can be found in Follies and Fallacies in Medicine (James MacCormick, Petr Skrabánek: 1989; available in Czech; Danish; Dutch; French; German; Italian; Spanish) and Cork-based Seamus O’Mahony’s books The Way We Die Now (2017), Can Medicine be Cured (2019) – both available in Swedish and Japanese – and The Ministry of Bodies (2021).

Although not by a doctor, Sinead Gleeson’s Constellations (2019; available in Brazilian Portuguese; Chinese – simplified; Dutch; French; German; and Korean) is recommended by the Irish Medical Times as a book for the bedside; this series of wide-ranging essays uses the experience of serious illness to examine culture, politics and what it is to be female providing “a profound rumination on womanhood in modern Ireland and the importance of artistic expression”.