“Nothing better to do at the weekend”

… “A few words” from Ireland

For over 90 years, every September a huge crowd of people (in recent years an average of 300 000) gathers in some part of Ireland for the National Ploughing Championships. The three-day event attracts competitors from all over the world, and in 2022, the World Ploughing Championships, originally to be held in Russia, were moved to run alongside the Irish ones. Irish ploughmen (so far, the international representatives have all been men though Irish women compete at national level) have won medals at these events in several categories including reversible ploughing – the mind boggles!

One of the categories of competition, loy digging, involves the use of a historic tool for digging by hand. This activity is now listed in the national inventory of intangible cultural heritage, which supports the recording, maintaining and handing on of traditional knowledge, skill and lore.

According to an unnamed ploughman at the 2017 World Championships in Germany, the Irish are good at ploughing “because they don’t have anything better to do at the weekend”. The English journalist from whose article this quote is taken points out that “[a] more plausible explanation is that, unlike in most countries, ploughing retains a certain status in Ireland.”

As a centuries-old practice in a primarily agrarian society for much of its history, ploughing is a key part of Irish rural life. Although the knowledge economy has taken over from agriculture as Ireland’s primary economic sector, farming remains an important activity, and the Championships still attract visitors from all around the country (including the ‘big smoke’) with its thousands of stands, and ancillary activities ranging from sheep shearing to the national brown bread baking competition.

Ireland Through the Lens

The Field (1990)is considered one of the classic Irish films, featuring a powerful performance by Irish actor Richard Harris. Land ownership, as the film demonstrates, has been an emotive issue in Ireland for centuries; it has been postulated that this was a contributing factor in the famines of the 19th century. The problems for the Irish peasantry during that period are tackled in more recent Irish films, Black ’47 (2018) and (Irish-language) Arracht (2021).

Please note, the Irish have a much more ‘accepting’ relationship with strong language than many other nationalities.

A Living Tradition*

If proof be needed that Ireland remains an agricultural country at heart, the fact that farmer Marty Mone’s music video Hit the Diff, a paean to a tractor gearing mechanism, garnered 1 million views could perhaps be used as evidence? On the other hand, alt-folk Junior Brother’s track, The Men Who Eat Ringforts, bewails the destruction of ringforts as agricultural land is commandeered for road and other construction projects.

Nonetheless country music, which back in the (oh so innocent) day was popularized in Ireland by (show) bands such as Big Tom and the Mainliners, remains part of the current Irish music scene as evidenced by performers such as Carlsbad and CMAT.

Quark

The importance of land in Irish life is of course reflected in its literature both fiction and non-fiction. In the latter category, Robert Lloyd Praeger’s The way that I went (1937) is a classic, while Manchán Magan’s 32 Words for Field (2020) explores the rich vocabulary in Irish of the rural environment.

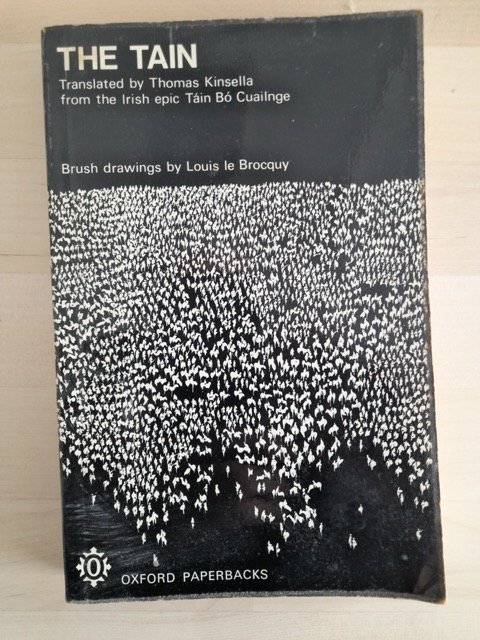

The Cow Book (John Connell, 2018), which is based around a calving season, is a pertinent reminder of the centrality of the cow in Irish life. The Táin Bó Cualighne (11th century ACE), an epic of Irish mythology, is the story of the attempt of Queen Medb of Connacht to steal the brown bull of Cooley from Ulster. The 1969 hardback edition of Thomas Kinsella’s translation, with illustrations by Louis Le Brocquy, is now a collector’s item. In paperback it is available in Chinese-simplified, French and Spanish.

As Nicholas Grene points out in an article for The Irish Times (2021), “once you [start] to look, farm scenes [are] everywhere in Irish writing”. He cites poets Patrick Kavanagh and Seamus Heaney, playwright Thomas Kilroy and writers Edna O’Brien and John McGahern among others.

In the context of the land, mention too must be made of Brian Friel’s play, Translations, which explores the dynamics of English Royal engineers coming to map an Irish-speaking town in Donegal (available in Bulgarian, Portuguese and Slovenian).